The Stories Behind the Songs of the Doors’ Last Hurrah, ‘L.A. Woman’

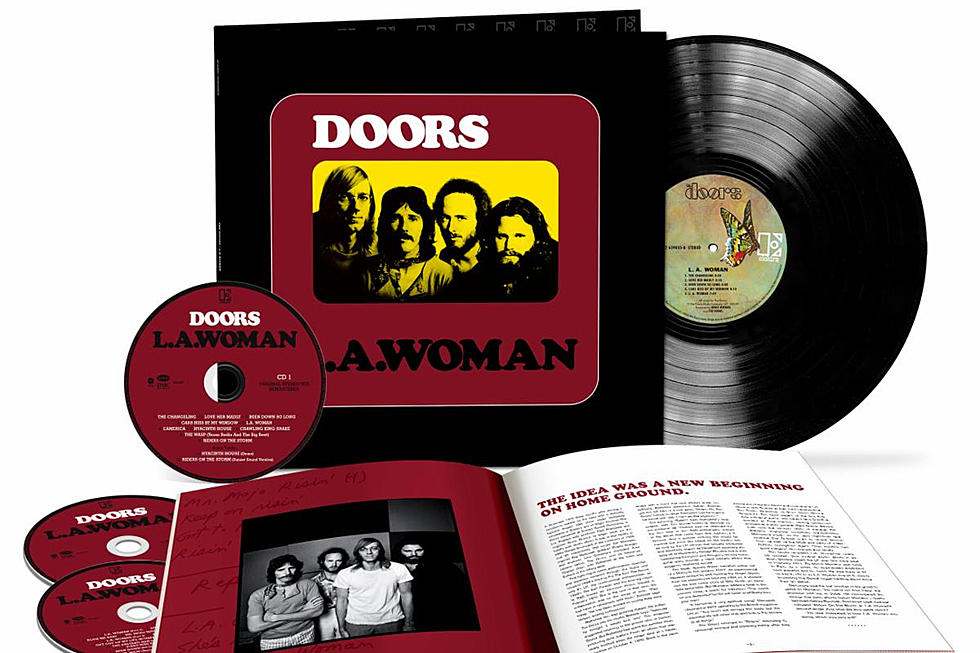

When L.A. Woman, Jim Morrison’s swan song with the Doors, was released on April 19, 1971, no one outside the band’s inner circle could have guessed that it would effectively end the quartet’s tale, much less mark the last recorded output of Morrison’s life. (The two post-Morrison Doors albums are a postscript at best).

The album has become such a staple of the classic rock canon that it's difficult to envision a time when it didn’t exist. But the Doors were attuned to all manner of artistic inspirations in music, film, and literature, and there were also dealing with some very intense situations by 1971. So a myriad of outside influences, both artistic and personal, went into the making of L.A. Woman.

"The Changeling"

The down-and-dirty, funky feel of the album’s opening track served notice straight out of the gate that this was not the strings-and-horns Doors of The Soft Parade but a sharp turn back towards the R&B and blues roots that were at the core of the band’s toolkit. Robby Krieger’s feral slide guitar sounds suspiciously reminiscent of Randy California, axeman from another pioneering L.A. outfit of the era, Spirit, who had just released their magnum opus and the final album by their original lineup, The 12 Dreams of Dr. Sardonicus, in November 1970, a month before work began on L.A. Woman. And when Jim sings “I’ve never been so broke that I couldn’t leave town,” it’s easy to imagine he’s already picturing himself in Paris. Though he didn’t split for France until weeks after the sessions, his bandmates have stated that he already knew he’d be going.

"Love Her Madly"

The Doors wanted “The Changeling” to the be the album’s first single, but the powers that be insisted on the more melodic, hooky Krieger composition “Love Her Madly.” It wasn’t the first time the man who penned “Light My Fire” would be tapped for a radio-friendly tune. While Morrison’s notoriously tempestuous relationship with Pamela Courson informed other songs on L.A. Woman, it was Krieger’s disagreements with his own girlfriend (who would later become his lifelong spouse) that inspired the lyrics.

"Been Down So Long"

There were some serious pressures weighing on Morrison (and by extension, his bandmates) during the sessions. In September 1970 he had been convicted of indecent exposure and public profanity at the band’s infamous 1969 Miami concert, and sentenced to six months behind bars. His case was still pending appeal, and the Doors’ reputation had made it difficult to book subsequent shows in the rest of the country. So its easy to understand the source of the the travails Morrison details in this tune. Its title could be a nod to Been Down So Long It Looks Like Up to Me, a landmark 1966 countercultural novel by author/songwriter Richard Farina, who died accidentally days after its publication.

"Cars Hiss by My Window"

At the end of the L.A. Woman sessions, which were short and spontaneous to begin with, the band dedicated a day to the bluesier tunes in their song bag, including “Been Down So Long,” “Crawling King Snake,” and this one. Morrison’s lament, “I’ve got this girl beside me, but she’s out of reach,” certainly seems indicative of the rough patch he and Courson were going through at that time. Krieger has called the low-key shuffle “our Jimmy Reed piece,” acknowledging one of the band’s key blues influences.

"L.A. Woman"

The lyrics for the Doors’ neon-lit salute to their home town seem to have been at least partly inspired by John Rechy’s transgressive 1963 novel City of Night, which chronicles the adventures of a young homosexual hustler who spends one chapter of the book plying his trade amid transsexuals and drag queens on the streets of Los Angeles. Morrison repeats the book’s title several times at the climax of the song, and the song's portrait of the L.A. streets’ seamy side certainly seems in line with Rechy’s prose.

"L’America"

This strange, ominous tune was originally intended for the soundtrack to Michelangelo Antonioni’s 1970 hippie flick Zabriskie Point, which attempted to capture the countercultural zeitgeist by using tunes from Pink Floyd, the Grateful Dead, the Youngbloods and others. But when the filmmaker visited the Doors’ HQ for a private performance of the song, he demurred. In Riders on the Storm, his memoir about his days with the Doors, drummer John Densmore reveals that “I took a trip down to L’America to trade some beads for a pint of gold,” actually refers to going down to Mexico to score some Acapulco Gold.

"Hyacinth House"

Doors keyboard man Ray Manzarek often reached outside of rock ‘n’ roll for his inspirations, tapping into jazz and classical music. On “Hyacinth House,” when it came time for his organ solo, Manzarek decided to pay homage to a favorite Chopin piece, "Polonaise in A-flat major, Op. 53," with a regal feel that somehow seemed to fit the otherwise intimate setting. Lyrically, Morrison was free-associating while brainstorming at Krieger’s home—the hyacinths were outside the guitarist’s window, and the line about lions was inspired by Krieger’s pet bobcat. Morrison’s troubles with Courson were likely behind the verse about him needing “someone who doesn’t need me.”

"Crawling King Snake"

Blues covers had always been a part of Doors concerts; the sound was one of the group’s fundamental building blocks. But only a couple of those covers ever made it into the studio. One was Willie Dixon’s “Back Door Man,” included on the band’s self-titled debut album, and the other was this doomy John Lee Hooker stomp. Given Morrison’s penchant for lizard and snake imagery, it’s easy to see why he would be attracted to this serpentine tune.

"The WASP (Texas Radio and the Big Beat)"

For all its poetic language, this song tells a very earthbound tale. It’s inspired by the sounds the young Floridian Morrison and Chicagoan Manzarek both heard drifting up from Tex-Mex border radio stations. And the blues clubs a teenage Morrison slipped into on the swampy side of Virginia when he lived there as a teenager are evoked in the verse about the sound that “comes out of the Virginia swamps cool and slow.”

"Riders on the Storm"

This moody, rainy-day masterpiece has its roots in a cowboy song. Krieger was messing around with the ominous, minor-key “Ghost Riders in the Sky,” a tune about undead cowpokes popularized by Vaughn Monroe in 1949. Sitting behind his electric piano, Manzarek monkeyed with the changes and jazzed up the feel and they were off to the races. But the idea of a murderous hitchhiker introduced in the second verse went back a long way with Morrison. He had written a screenplay about a homicidal hitchhiker, which was eventually made into an unreleased short film by Morrison and a few friends under the name HWY (for highway). By the time it was done, the hitcher was no longer a killer but merely a wanderer.

On the philosophical side, it’s been suggested by academicians that the verse that ends both the song and the album -- the one that goes “Into this house we’re born / Into this world we’re thrown / Like a dog without a bone / An actor out on loan” -- is straight out of Nietzsche and Heidegger, whose existentialist ideas Morrison was exposed to at least as early as his time at UCLA, and possibly even in his high-school bookworm era. It would be the last recorded statement he’d leave behind.

More From 92.9 WBUF